Real estate investing offers tremendous wealth-building opportunities, but understanding the tax implications can mean the difference between mediocre returns and exceptional profits. While rental income and appreciation drive returns, taxes can quietly erode 30-40% or more of your gains if you’re not careful. The good news? With proper planning, real estate offers more tax advantages than almost any other investment vehicle. This guide breaks down every tax you’ll encounter as a real estate investor and reveals strategies to legally minimize or eliminate them. Whether you’re analyzing your first deal or optimizing a portfolio, mastering these tax concepts will dramatically improve your bottom line.

Types of Taxes Real Estate Investors Face

Property Taxes

Property taxes are the most persistent tax burden for real estate investors, due annually based on your property’s assessed value. Unlike other taxes you can defer or avoid, property taxes must be paid every year regardless of whether your property generates income. Most jurisdictions calculate property tax by multiplying the assessed value by the local tax rate (often expressed in “mills” where one mill equals $1 per $1,000 of assessed value).

For investors, property taxes directly impact cash flow and must be accurately projected in any deal analysis. A property with $24,000 annual rental income and $3,000 in property taxes effectively reduces your gross yield by 12.5%. Rates vary dramatically by location—from under 0.5% in Hawaii to over 2% in New Jersey—making tax considerations crucial when choosing investment markets.

Here’s an important point I often make about appreciation: while we talk about appreciation being largely tax-deferred until you sell (for capital gains purposes), that’s only mostly true. As your property value increases, so does your assessed value in most cases, meaning you’re paying incrementally higher property taxes on that appreciation every single year. It’s like paying a small annual tax on unrealized gains.

Strategies to reduce property taxes include challenging assessments (especially if comparable properties have lower valuations), applying for homestead exemptions on eligible properties, seeking tax abatements in designated development zones, and considering locations with favorable tax policies or caps on annual increases.

Capital Gains Tax

Capital gains tax applies when you sell an investment property for more than your adjusted basis (purchase price plus improvements minus depreciation). The rate depends on your holding period: properties held over one year qualify for long-term capital gains rates (0%, 15%, or 20% based on income), while shorter holdings face ordinary income tax rates up to 37%.

Your taxable gain equals the sale price minus selling costs, minus your adjusted basis. If you bought a property for $200,000, claimed $30,000 in depreciation, made $20,000 in improvements, and sold for $300,000, your gain would be $110,000 ($300,000 – $190,000 adjusted basis). This doesn’t include depreciation recapture, which is taxed separately.

The primary residence exclusion offers massive tax savings—single filers can exclude $250,000 of gains ($500,000 for married couples) if they’ve lived in the property two of the last five years. Some investors strategically move into rentals before selling to qualify.

Additional strategies include timing sales for years with lower income (perhaps after retirement), harvesting losses from other investments to offset gains, using installment sales to spread gains over multiple years, and combining with 1031 exchanges to defer taxes indefinitely. Remember that state capital gains taxes may apply on top of federal taxes.

Depreciation Recapture Tax

Depreciation recapture is often the surprise tax that catches investors off guard. While depreciation deductions reduce your taxable income during ownership, the IRS “recaptures” these benefits when you sell, taxing the accumulated depreciation at a flat 25% rate (assuming you’re in a tax bracket of 25% or higher).

This tax applies regardless of whether your property actually depreciated in value. If you claimed $50,000 in depreciation deductions over your holding period, you’ll owe $12,500 in recapture tax upon sale, separate from and in addition to capital gains tax. The recapture applies to the lesser of the gain or the total depreciation claimed.

Depreciation recapture significantly impacts exit strategies and True Net Equity™ calculations. A property showing a $100,000 gain might net considerably less after paying both capital gains and recapture taxes. This hidden tax burden can reduce proceeds by 25-35% if not properly planned for.

Strategies to manage recapture include using 1031 exchanges to defer the tax indefinitely, timing cost segregation studies to front-load benefits when tax rates are higher, holding properties until death for a stepped-up basis that eliminates recapture, and considering the trade-off between current deductions and future recapture liability. Some investors intentionally forgo depreciation deductions, though this rarely makes financial sense given time value of money.

Transfer Taxes

Transfer taxes are one-time taxes imposed when property ownership changes hands, charged by state and/or local governments. These taxes typically range from 0.1% to 2% of the sale price, though some areas like Washington D.C. can exceed 3% for high-value properties. Unlike most taxes, who pays varies by location—sometimes it’s the seller, sometimes the buyer, and sometimes it’s split.

For real estate investors, transfer taxes directly impact closing costs when buying and net proceeds when selling. A $500,000 property sale with a 1.5% transfer tax means $7,500 less in your pocket. When calculating True Net Equity™ or analyzing potential returns, these taxes must be factored into your projections. Many investors overlook transfer taxes during initial analysis, leading to surprises at closing.

The impact compounds for active investors. If you’re flipping properties or have a shorter hold strategy, transfer taxes on both purchase and sale can significantly erode margins. A fix-and-flip with 2% transfer taxes on each transaction loses 4% to these taxes alone.

Strategies include negotiating who pays during contract negotiations (in flexible markets), using entity transfers instead of property transfers where legally permissible, considering locations with lower or no transfer taxes for active trading strategies, and factoring these costs into your minimum profit requirements. Some jurisdictions offer exemptions for certain transfers, such as between related entities or for affordable housing.

Income Tax on Rental Income

Rental income is taxed as ordinary income at your marginal tax rate, making it potentially the highest-taxed component of real estate returns. However, real estate offers numerous deductions that can dramatically reduce or eliminate taxable rental income. The IRS considers rental activities as passive income, subject to specific rules and limitations.

Deductible expenses include mortgage interest, property taxes, insurance, repairs and maintenance, property management fees, utilities (if landlord-paid), advertising, professional services, and depreciation. The key is distinguishing between repairs (immediately deductible) and improvements (capitalized and depreciated). Fixing a broken window is a repair; replacing all windows is an improvement.

Passive activity loss limitations restrict deducting rental losses against other income if your adjusted gross income exceeds $100,000 (phasing out completely at $150,000). However, unused losses carry forward indefinitely and can offset future rental income or be claimed upon sale. Real estate professionals who materially participate in rental activities can avoid these limitations entirely.

Strategies for minimizing rental income tax include maximizing legitimate deductions through proper documentation, timing repairs and expenses strategically, considering cost segregation for accelerated depreciation, qualifying as a real estate professional if you’re active enough, and using rental losses to offset other passive income. Some investors strategically leverage properties to maximize interest deductions while building equity through appreciation.

Tax-Saving Strategies

1031 Tax-Deferred Exchanges

The 1031 exchange is the real estate investor’s ultimate tax deferral tool, allowing you to swap one investment property for another while deferring all capital gains and depreciation recapture taxes. Named after Section 1031 of the tax code, this strategy lets you compound your entire proceeds into the next investment rather than sharing 20-40% with the IRS.

The rules are strict but manageable: you have 45 days to identify replacement properties and 180 days to close. The replacement property must be of equal or greater value, and you must reinvest all proceeds. You can’t touch the money—it goes through a qualified intermediary. While you can trade up, down, or sideways in property type (apartment for retail, land for rentals), both properties must be investment or business use.

Advanced strategies include reverse exchanges (buying before selling), improvement exchanges (using proceeds for renovations), and Delaware Statutory Trusts for passive investment options. Some investors chain multiple 1031 exchanges over decades, deferring taxes indefinitely until receiving a stepped-up basis at death.

Timing Strategies

Strategic timing can save thousands in taxes. Selling properties during low-income years—perhaps after retirement or during a business downturn—can reduce capital gains rates from 20% to 0%. Similarly, bunching deductions by prepaying expenses or timing major repairs can maximize benefits in high-income years.

Depreciation elections offer timing flexibility. Cost segregation studies can accelerate depreciation, creating larger deductions now at the cost of higher recapture later. This makes sense if you expect lower future tax rates or plan to 1031 exchange indefinitely.

Entity Structuring and Advanced Strategies

Proper entity structuring provides both asset protection and tax benefits. LLCs offer flexibility and pass-through taxation, while S-Corps can reduce self-employment taxes for active investors. Self-directed IRAs enable tax-free or tax-deferred growth but with strict rules about personal use and transactions.

Opportunity Zones offer exceptional benefits for patient capital: defer capital gains until 2026, receive a 10% basis step-up after five years, and pay zero taxes on Opportunity Zone appreciation if held for ten years. The catch? Investments must be in designated low-income areas and substantially improve the property.

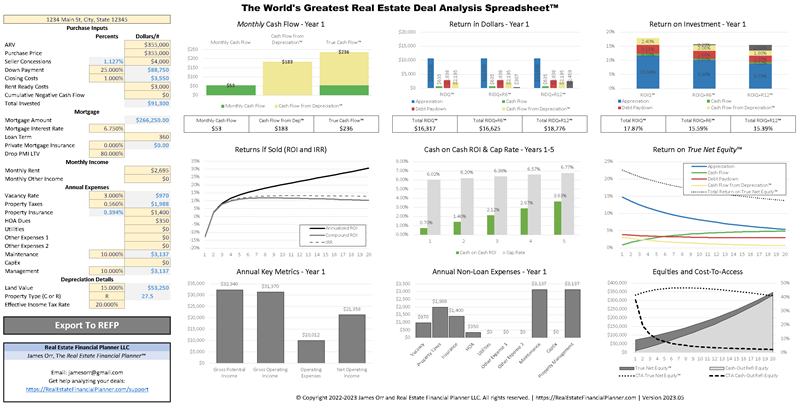

Integration with Deal Analysis Tools

When using The World’s Greatest Real Estate Deal Analysis Spreadsheet™, accurately projecting property taxes is crucial for cash flow analysis. A common mistake is using current taxes rather than post-purchase reassessed values. In many jurisdictions, sales trigger reassessment to market value, potentially dramatically increasing property taxes.

For exit planning, True Net Equity™ calculations must factor in both capital gains and depreciation recapture taxes. A property showing $200,000 in equity might yield only $140,000 after taxes. Transfer taxes further reduce proceeds. These tax impacts dramatically affect your True Net Worth™—the after-tax value of your portfolio if liquidated today.

The most sophisticated investors model tax-adjusted returns. A 15% pre-tax return might only be 10% after-tax, while a tax-advantaged strategy yielding 12% might net 11% after taxes. Understanding these differences drives better investment decisions.

Common Tax Mistakes to Avoid

The biggest mistakes include poor recordkeeping (making deductions hard to justify), mixing personal and business expenses (triggering audits), missing important deadlines (like 1031 exchange windows), and not consulting professionals for complex situations. Many investors also fail to track improvements separately from repairs, losing valuable basis additions that reduce capital gains.

Entity structure mistakes are costly. Holding property in the wrong entity can trigger unnecessary taxes or lose benefits. Similarly, not understanding passive loss limitations leads to unused deductions. Some investors overlook state taxes, focusing only on federal implications.

Planning Your Tax Strategy

Tax planning isn’t a year-end activity—it’s an ongoing process. Quarterly estimated payments prevent penalties for rental income. Year-end moves might include timing repairs, prepaying expenses, or accelerating depreciation through cost segregation. Document everything: receipts, mileage logs, and property improvements.

Consider professional help for complex situations. While software handles basic rental income, scenarios involving multiple properties, 1031 exchanges, or entity structuring benefit from expert guidance. A good CPA specializing in real estate often pays for themselves through tax savings.

State considerations matter increasingly. Some investors relocate to tax-friendly states before major sales. Others focus investments in states without income tax. Property tax caps, like California’s Proposition 13, can provide long-term benefits for buy-and-hold strategies.

Conclusion

Taxes represent one of the largest expenses for real estate investors, but also offer the greatest opportunity for optimization. Understanding property taxes, capital gains, depreciation recapture, transfer taxes, and income tax on rentals forms the foundation. Strategies like 1031 exchanges, strategic timing, and proper structuring can defer or eliminate massive tax liabilities.

The key is integrating tax planning into your investment strategy from day one. When analyzing deals, factor in all tax implications. When operating properties, maximize deductions while maintaining proper documentation. When planning exits, consider tax-efficient strategies that preserve more of your hard-earned equity.

Real estate’s tax advantages are one reason it builds more millionaires than any other investment vehicle. By mastering these concepts and implementing appropriate strategies, you’ll keep more profits working for you rather than going to the IRS. The difference between average investors and wealthy ones often comes down to understanding and optimizing taxes. Now you have the knowledge—it’s time to put it into practice.